Garbled Circuits

Mon 30 October 2017

Mon 30 October 2017

Note

This is a part of a series of blog posts I wrote for an Independent Study on cryptography at Oregon State University. To read all of the posts, check out the 'Independent Crypto' tag.

Let's imagine you are a billionaire. You want to know if you have more money than your billionaire friend Bob, but for some reason it's very faux pas to let anybody know how much money you have, even your good friend Bob.

But you're a billionaire! You're not used to the phrase "that isn't possible". In your frustration you try to figure out if you can use some of your billions to find a solution.

The first solution you come up with is Trusty Tina. You tell Tina how much you make, Bob tells Tina how much he makes, and then Tina tells both of you who makes more.

The only problem is that Tina isn't that trustworthy, her parent's just named her that. Like... you wouldn't trust her with your life or anything. You could pay her to keep your assets secret but Bob might pay her a bit more reveal your number to him. Tina reminds you of this so you have to pay her more to keep the secret, and eventually you have an arms-race type situation at hand. With your cunning accountant skills you can already tell that Tina might be more trouble than she's worth.

If you won't tell Bob directly, and you can't depend on Manipulative Tina, is there any way to determine out who has more money?

Yes.

The problem above is the Millionaires problem [9] and it is solved by the use of 2-party secure function evaluation (SFE). The general idea [4] is that you have a function f which takes as input x and y. This function is garbled by one of the two parties into f' and the inputs are garbled into x' and y' by each of the parties. f'(x', y') == f(x,y) but does not leak any of the inputs, because x and y were obfuscated.

In other words...

Note

The first half of this post focuses on honest garbled circuit uses, meaning both parties are acting honestly (and don't pull any fast-ones).

The latter portion focuses on problems with that 'vanilla' garbled circuit implementation and potential solutions.

How does Alice actually... 'garble' a circuit? It sounds kinda dirty.

Each gate (OR, AND, XOR, etc) has two inputs. Stick with me. Each input is encrypted. Keeping up? So you need a key to use each gate. It gets better. But if you have the keys, you don't know which key corresponds with a 1 or a 0 so you can compute a function without knowing the actual values you put in. Whoa.

Let's use the OR gate as an example.

Remember truth-tables for OR? Here's a reminder:

| OR | 0 | 1 |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

This table is going to be important for Alice's part of this dance.

Alice definitely does the heavy lifting in this transaction.

| OR | 0 | 1 |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | B00 = 0 | B01 = 1 |

| 1 | B10 = 1 | B11 = 1 |

| OR | 0 | 1 |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | E(Kx0||Ky0, B00) | E(Kx0||Ky1, B01) |

| 1 | E(Kx1||Ky0, B10) | E(Kx1||Ky1, B11) |

Bob has enough information to get one of the four possible outputs of the circuit, but doesn't know if Alice's input is a 1 or a 0.

Importantly, while Bob can share the output of the circuit, he should not share his input. That would make using OT (step 6) obtuse.

Note

The UTF-8 Padlock symbol doesn't render on my browser because I seem to have gone back in the time to the late 90s. Being stuck in the past, we have to comprmise. The ⛨ symbol is meant to represent a lock and the ⚿ represents a key.

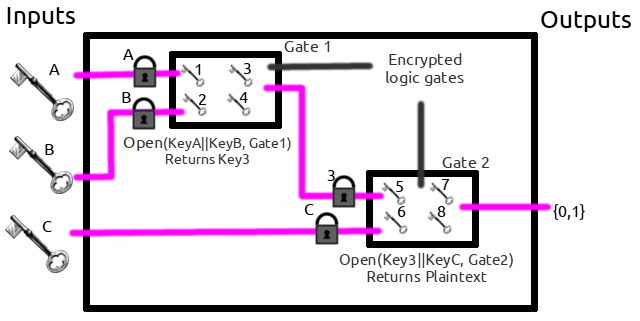

Multiple gates can be connected together to build more complicated circuits. One important difference is that while each intermediate circuit still has four cipher-texts, for the four outcomes of a truth-table, those decrypt to a key and not a 1 or 0. The only gates which decrypt to a plain-text of 0 or 1 are output gates, not the intermediate gates.

Note

PSST Check out the end of this post for a GAME!

There are a few important flaws in the security of garbled circuits as they have been described. The first is that although Alice and Bob agree on a circuit to garble there is no guarantee that the circuit one is evaluating (if you're Bob) is the circuit you agreed upon.

For example:

To prevent the above adversarial attack we do something called "Cut-and-Choose". This is when Bob checks Alice's work to make sure she's not cheating.

Remember that Alice and Bob agreed on a given circuit.

This ensures that Alice is not nefarious to some statistical certainty. She had control over how the circuits were garbled but she does not have control over which are revealed or evaluated. If she made one (or two or three...) nefarious circuits that bad behavior is probably revealed in step 2, if all the checked circuits are good Alice is probably being honest.

This doesn't break garbled circuits for the following reasons:

As M grows and N approaches M this method gets more secure at the cost of computation cycles and bandwidth in transferring the garbled circuits.

I'm definitely not a circuits person. You can show me a circuit diagram and I'll say "Yep, that's a circuit. What's it do?" I couldn't even even identify which gate is which without Wikipedia.

I was told during my research for this post that XOR gates are very popular with garbled circuit design, and more broadly circuit design in general. This was shared to me in the form of a cryptic hint so I figured I'd investigate and share my findings here.

As it turns out the Wikipedia page notes that this XOR optimization exists and even cites the original paper published on the topic. [6]

The jist of this optimization is that one can very efficiently garble an XOR gate such that the output of the gate is encoded as the XOR of the keys used to unlock the gate and some known global constant. This is in contrast with the implementations discussed in the beginning where each gate had to be decrypted with two cipher-texts and revealed another key.

Basically using XOR, which is pretty fast, we can avoid generating four keys per gate and instead craft 1 key which is produced as the result of 'unlocking' a gate.

Put a bit more formally:

Given a gate G with input wires A and B and output wire C and a random string R, the garbled gate is obtained by XORing the garbled gates inputs C1 = C0 ⊕ R:

C0 = A0 ⊕ B0 = (A0 ⊕ R ) ⊕ (B0 ⊕ R) = A1 ⊕ B1C1 = C0 ⊕ R = A0 (B0 ⊕ R ) = A0 ⊕ B1 = (A0 ⊕ R) ⊕ B0 = A1 ⊕ B0

Note

LETTER{0,1} is short-hand for the True or False output of the given gate.

This isn't super intuitive, and honestly I just put those equations up there to prove that I read a paper about this.

The main takeaway is that 'free XOR' saves us computation generating and processing cryptographic keys by simply performing the XOR operation. This optimization is so powerful that using mostly XOR gates makes garbled circuits notably faster and more useful for secure computation. [8]

This was the first source I checked out to get a feel for how difficult garbled circuits are as a topic. It quickly glanced at the basics of garbled circuits and then quickly went into the optimizations on garbled circuits. This was overwhelming, but as I started to learn more about garbled circuits and filled in the knowledge gaps it gained significant value.

It's a great talk about Garbled Circuits which wasn't ideal for beginners, but did give me a good breadth of the topic and what I could dive into.

Note

Yes, the name is a misnomer. The goal is to evaluate a garbled circuit, but that just doesn't roll off the tongue the same.

| [1] | SFE: Yao's Garbled Circuit, Published by engr.illinois.edu, for the course CS 598, Fall 2009. https://courses.engr.illinois.edu/cs598man/fa2009/slides/ac-f09-lect16-yao.pdf |

| [2] | Foundations of Garbled Circuits, Written by Mihir Bellare, Viet tung Hoang, and Phillip Rogaway, Published October, 2012. https://eprint.iacr.org/2012/265.pdf |

| [3] | What exactly is a "garbled circuit"? Asked by user Ella Rose, Answered by user Mikero on on July 27, 2016. https://crypto.stackexchange.com/a/37993 |

| [6] | (1, 2) Improved garbled Circuit: Free XOR Gates and Applications, Written by Vladimir Kolesnikov and Thomas Shneider, Published July 2008. http://www.cs.toronto.edu/~vlad/papers/XOR_ICALP08.pdf |

| [7] | Why XOR and NOT is free in garbled circuits Asked by user Jason, Answered by user Mikero on February 28, 2017. https://crypto.stackexchange.com/a/44278 |

| [8] | (1, 2) A Brief History of Practical Garbled Circuit Optimizations, Presented by Mike Rosulek, Published by the Simons Institute, June 15, 2015. https://youtu.be/FTxh908u9y8 |

| [4] | To completely level with you, it's been anecdotally proven that there is at least 1 definition of Garbled Circuits for each paper on the topic. |

| [5] | Oblivious Transfer has been described to me as:

This is a cryptographic primitive which is very useful for tasks like generating Bob's input to the garbled circuit f'. |

| [9] | The original problem was developed in the 80's. This post adjusts the scenario for inflation. |